Pair Programming

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. | ||

In Germany, we have a cynical way of defining 'TEAM' as an acronym:

Toll, ein Anderer macht's.

It basically means: 'Great, someone else will do it!'. Does this sound familiar?

Why should two or more people be assigned to a single problem when each of them could solve a problem on their own?

And how can you concentrate when someone is constantly looking over your shoulder?

My personal experiences coincide with studies on this topic.

The Sceptic

I still remember the day I first heard about pair programming.

At the time, I was still a junior developer and I was sitting in a comfortable two-person office with my mentor at the time.

He had just read an article that mentioned pair programming.

He made fun of it and said, ‘Do you know what pair programming is?’

I said no.

‘It's where one developer sits on the other's lap and one uses the mouse while the other uses the keyboard,’ he laughed.

That was the end of the conversation on that topic.

The First Contact

Years later, when I was already working for another employer, I came in contact with that term again.

I was the sole developer in a project that had already grown too large for one man long before I even started there, and I needed support.

After a lengthy search, we finally found someone with even more experience than me. He also said, that it was natural for him to do the onboarding in pair.

I thought back to what I had previously heard about that practice, and even though I was relatively sure that this wouldn't mean one of us sitting on the lap of the other one (I certainly hoped so), I was very skeptical about how this would work.

So I told him truthfully that I had never done that before, but this wasn't a problem for him.

He had already gained valuable experience with a former employer.

Not an easy start

Frankly, the beginning of this felt pretty exhausting.

I was used to working alone, and I easily got nervous when someone looked over my shoulder.

Of course I've collaborated directly with colleagues before, but these were usually very contained sessions for specific problems and more the exception than the default.

Now I had a constant neighbor who asked questions about what I did and why I did it like that.

This was annoying at times and it was easy to misjudge several of the questions as (personal) attacks.

None of them were meant like that, of course, but if you're too much used to work alone, it's easy to fall into that trap.

Nevertheless, I soon realized how much progress we made.

While I was explaining the system to my colleague, I learned a lot of things from him.

It was especially interesting to see how much explaining the system to him helped me to improve my own understanding.

Explain to understand

Actually, this is a method I've been using for myself for quite some time now.

When I go for a walk, do sports, take care of the household, or do other activities that don't require much thought, I like to explain things to myself in my internal dialogues.

I don't know when I started doing this (I am pretty sure that I was still in my teens) or how I came up with it.

It's just something I've been doing for a long time, and it helps me deepen my understanding of certain concepts.

Explaining is an essential part of pair programming.

And it's a lot more effective if you have an actual person to talk to, who actually asks questions, or—even better—brings other perspectives and counterarguments.

If you're just working for yourself, it's easy to just do something without actually thinking about it. Just working by muscle-memory.

But if you're working together with someone, you get used to explaining properly what you're actually doing before just typing away.

At the same time, you get direct feedback, especially if you forgot something or your partner has an idea for an alternative approach.

The culture of debate

Obviously, we didn't agree on everything. Quite the contrary, actually.

I was (and still am) a big proponent of KISS, while my colleague threw Clean Code, SOLID, and DDD at me.

If used properly, all these concepts work well together, but we were both too dogmatic in our approaches.

He called my code 'spaghetti code,' and I called his 'code overengineered.'

Our very different perspectives clashed with each other.

We often moved our discussions outside. For one thing, we were in one big office, and our constant talking was annoying enough for the people around us.

We also welcomed the fresh air (in the case of my colleague, nicotin-enriched).

One day, another colleague from operations asked us if we made up.

We were confused, and she had to explain to us that our constant discussions looked like arguments from the outside.

Of course some discussions could have gone better, but for us, it was the way to find the sweet spot between our very different methods.

Criticism

It is too easy to take criticism on our own work personally, and it is a valuable skill not to do so, but to approach the matter objectively.

In my opinion, this is one lesson that is not taught enough.

Before I became a software developer, I first trained as a designer.

There, this was the first lesson we were told by the teachers.

When presenting the results of your work to someone else, it doesn't matter what you personally think of your work.

Most feedback you get from others is very valuable, and you should never take it personally.

Instead, ask: ‘What exactly isn't working?’ ‘What can I do better?’

In the best-case scenario, you have someone sitting in front of you whom you can ask specifically: ‘How can I do better?’

In the worst case, you get a ‘No idea, you're the expert’ in return.

But even then, you can view the work you've done as training. So you keep going until you get the right result.

Practice makes perfect.

In pair programming, being criticized is part of the process, as much as criticizing yourself.

There are almost always different ways to tackle a problem, and we often had to continue with an "agree to disagree".

Part of the skills you develop when doing pair programming is communicating your own train of thought, questioning different variants, and evaluating the possible approaches.

Results

What happened during our close collaboration?

I learned more advanced principles and systems of software development.

My initial skepticism against automated testing was turned around 180°, and I am now in strong support of TDD.

I have now specialist literature such as Fundamentals of Software Architecture, Vaught Vernon's Domain-Driven Design, and A Philosophy of Software Design lying around everywhere in the house, while I follow YouTube channels such as Modern Software Engineering and Arjan Codes.

And even though I knew before that communication is crucial, this became even more obvious in this context. My approach to communication in general improved, and my thirst for knowledge increased.

This had a positive effect on my own communication overall, and not just with that one colleague.

It is always great to see other solutions popping up as soon as new perspectives are added to the mix.

But I am not the only one who learned something new. Plenty of ways he proposed turned out to be overengineered, and we learned a great deal not only about how to implement certain architectural concepts but also when and where to do this (and when not).

Suffice to say, my colleague infected me with excitement for pair programming, and we continue to see situations where this approach has a very positive effect on projects (or could have, if it would be implemented).

Remote collaboration

In 2020 we were suddenly sent to work from home.

To be honest, I didn't like working from home. I've tried it before, but there was just too much distraction.

I didn't even have my own room at home, and I had to sit in my daughter's room for the first year. At least she was just born in 2020, so she didn't care that much at that time.

But still, this was my workplace now.

Oh my.

Right on the first day, we all logged into MS Teams, and we started working while in the call.

That actually worked great. We did not have to cuddle around one table, always struggling with the other person's keybindings when switching roles.

Admittedly, the tools for remote collaboration weren't that great, and we've had some technical difficulties, but all in all, work actually got more comfortable and even - difficult to believe - more productive.

Mob Programming

As if the pandemic wasn't enough, we also got a new project, including a new team that had just been thrown together. We've had some initial difficulties with both.

So we spontaneously decided to try out mob programming.

Instead of everyone doing their own thing, we all joined a collaborative call, and we started working on one task at a time with the whole group.

We were surprised again by how great that actually worked.

Of course I was the skeptic again (I actually had that nickname for a while), and I expected the same to happen as with every group project: one or two people do the work, and the rest do whatever.

Instead, I was surprised as everyone actually got involved right from the start. Even more surprising, that included people who you usually had to ask for results multiple times before you got anything out of them. They were actively giving valuable input.

We somehow kept motivating each other, and the biggest problem was often to actually stop working at the end of the day.

After a few days, we started parallelizing work through pairs or small groups that opened their own calls.

Of course everyone was free to work on their own as well. That was not only before and after our calls, but everyone was free to just tell us that they're out and leave the call for as long as they needed.

Our group calls weren't mandatory, but everyone joined anyway.

At some point we were in a mode where our call worked similar to a large office. We joined the call, said ‘Hello,’ muted the microphone, and started working.

If someone had a question, they could just ask it in the call (or write a message in the chat), and now and then smaller groups of people created their own calls to concentrate their focus on a specific task.

It was an interesting way to work, and we often elaborated on everything, including personal stuff; we cursed, cheered, and laughed a lot.

Of course, one must also bear in mind that it was a time of social isolation, which we also compensated for in this way.

We were also happy that we already knew each other personally from having met before, even though that was only for a few months for some of the team members.

Going back to "normal" work

Now we got the next project, but this time under new leadership.

We had to work with a specific framework, which is a pretty good example if you want to show an example of overengineering to anyone.

But only experts in the field were recruited, so it was also expected from us to work individually on each task.

Why should multiple people work together on one task when they could work on an equal number of tasks in parallel?

What about information sharing?

That's what meetings and code reviews are for!

Every task has to be reviewed and approved by multiple people from the team.

Additionally, every morning we had a stand-up meeting ceremony. It took around 45 minutes.

Too many people will recognize this; it was one of the worst variants of ‘Scrum.’

But I don't want to go too deep into that; this is about another topic here.

So how did the process look there?

First, every task was discussed in detail with the whole team.

The goal was that every dev could pick any task and finish it without having to ask any questions.

Then, everyone picked their task and started working on it. If you thought you were done, you moved it to the review stage and added all developers to the review.

To not let the task lie too long in the review stage, we had the agreement to look at every review as soon as possible.

So everyone stopped what they were doing and opened both the pull request and the linked ticket. Then each one of us had to read through the ticket to remember what it was about and then look at the proposed solution.

That wasn't easy, especially in combination with the complex framework in use. Often we had to actually check out the changes locally to test the feature (or bug fix) on our own machines. That took time and effort.

There weren't many tasks with no feedback. Something almost always came up.

Since these reviews took some time, the developer waiting for feedback usually started the next task. Another change in context.

The reviews often lead to discussions in the comments, and several times, tasks had to start anew or were even completely stopped.

Almost none of these tasks were in development for much less than two weeks at that point.

So we had a system where we didn't really work together but in parallel, with only the reviews being the exception that also threw us out of our current task. These reviews were almost exclusively the place for proper feedback, which usually was too late at that point.

Of course there were other problems in that project, but several of us recognized at that time that the negative impact of pair programming maybe wasn't as great as we previously thought.

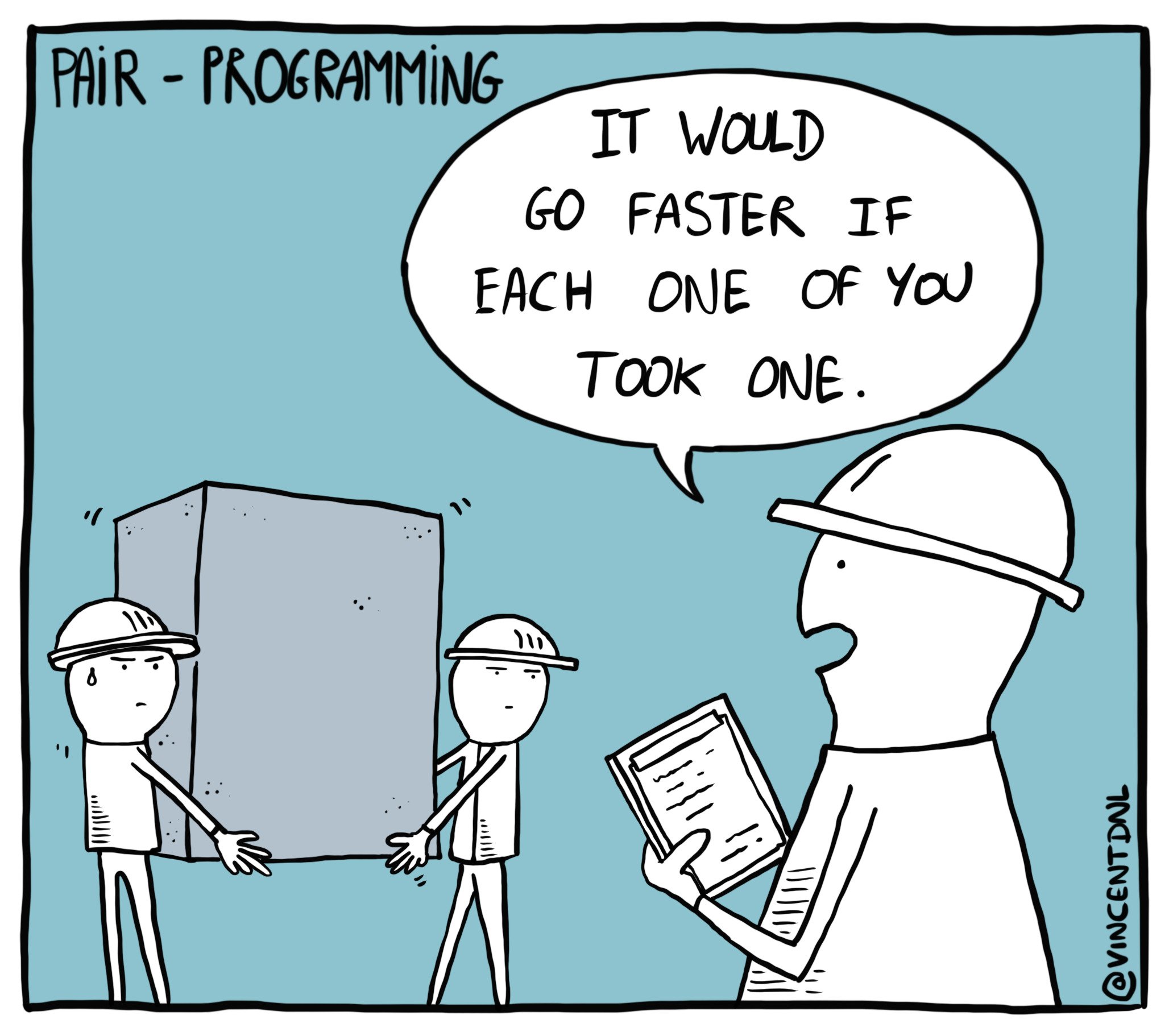

Image credit: "Pair Programming" by Vincent Déniel is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

The research

I don't even remember how, but at some point I landed on this blog page (only in German, sorry): Der lise Blog. Ist Pair Programming Zeitverschwendung?

It's more an advertisement for the services the company offers, and I never had any contact with them.

Also, my experience with pair programming is different from the one they describe in the text.

But the most interesting part for me was the study they linked to: The Costs and Benefits of Pair Programming

I can only strongly recommend reading the linked document. It's a short one. Here is a summary:

Through the implementation of pair programming, tasks took about 15% longer to complete.

But it also led to:

Lower defect rate:

The results contained significantly fewer bugs.

This more than mitigated the additional time, since there was a significant decrease in follow-up tasks for refactoring and especially bug fixing.Cleaner code style:

Developer pairs tend to create solutions with less code.

The collaboration encourages consideration of a greater number of alternatives, which promotes the development of a better outcome.Continuous reviews:

Direct collaboration is comparable to continuous design and code reviews. Issues are found a lot more often already while they're being typed, which decreases the cost of correcting them significantly.

That also matches my previously described experience and results in the already mentioned lower defect rates.Improved problem solving:

Pairs report that they can solve problems faster.

This is often described as ‘pair relaying,’ in which partners take turns contributing ideas and thus tackle difficult tasks together.Better knowledge sharing:

In pair programming, knowledge is continuously shared.

This includes everything from the methods as well as the usage of tools and the work itself.Improved team building and communication:

The work method requires a lot (almost constant) communication with each other.

This can improve the team dynamic, the information flow, and the overall effectiveness.Reduction of personal risks:

Since multiple people work on these tasks, the knowledge is always shared.

This reduces the risk that only one person has the knowledge about a certain system, which can lead to issues if they're not available (‘key person risk’ or ‘bus factor’).Higher employee satisfaction:

Developers who work in pairs usually find the experience more enjoyable and are more confident about the quality of their work.

It is nice to see how much our own experience is matched by that study.

But of course, you also have to consider the negative aspects of using this method.

According to the study, there is an initial additional cost. This involves the acclimation phase in which the developers have to get used to the method, as well as the cost of the additional communication.

Many people also have an initial skepticism (as had I). This usually pays for itself later on when there are fewer defects in the system. Many don't like to hear that and prefer the faster development right from the beginning.

The method can also lead to personal conflicts. Not everyone likes to work closely together, and some of them have become too entrenched in their lone-wolf mentality.

And everyone has to have some time for themselves to really focus on something.

Should we only work in pairs from now on?

No. If someone tells you that they found the silver bullet to solve all problems, run!

It's the same with pair programming. I am definitely a strong proponent for this method, and I have only had positive experiences with it for now.

At the same time, it's hard for me to find any arguments against it.

But starting with this is usually not that easy, and everyone needs to have their space. The longer one has worked alone, the harder it usually is to adapt to this.

I would also apply the principle of ‘people over processes’ from the Agile Manifesto here.

I'd definitely recommend trying it out for at least a few weeks. It took me certainly longer than one week to see the benefits.

You don't have to introduce it with a crowbar either.

Depending on the team size and availability, one could add a fixed time slot for pair (or mob) programming and modify it according to the results. Or the team organizes itself internally to work together for a few hours (or at least minutes), maybe based on the tasks.

When being open to it, the advantages are obvious, and the positive effects should be visible after a few weeks.

Summary (tl;dr)

Pair programming is a good methodology for sustainable software development.

Getting started is not always easy, and it depends heavily on the previous experience and character of the people involved. Measured on the individual tasks, development time for new features is slower, but that time is offset by higher quality, better maintainability, fewer defects, and improved internal team communication.

Incidentally, onboarding is also covered, as new developers can be easily integrated into the process.

All this is not only my personal experience (including that of several of my colleagues), but also backed by studies.

Final words

I read a lot about software development and enjoy seeing what others have to say on the subject.

Interestingly, I hardly ever see pair programming mentioned. But when it is, it's almost always in a positive light.

I find it strange and, at this point, even incomprehensible why pair programming isn't the standard practice, given that it offers so many advantages.

The temptation to throw several people at just as many topics at once appears to be too strong.

Perhaps too many people don't have the mindset to really get involved.

Or the initial hurdle is too high for some to overcome.

I can only advise you to give it a try.

Comments